7. Pottery Technology 1

| 864 Page: 70 of 418 Go To Page: | ◁◁ First | ◁ Previous | Next ▷ | Last ▷▷ |

Stoneware and porcelain glazes could be applied to the leather hard body (unfired) and both body and glaze fired to the same high temperature, as was done in China, so it was potentially more economic having only a single firing. In this case the glazes had to be of a material that melted at a temperature slightly lower than the maturing temperature of the body, so that it melts and flows over the surface before the body changes state. However it cannot have such a low melting point that it flows off the body or volatilises.

The discovery of “salt” glaze is a mystery, it may have been a culinary accident with cooking and firing becoming mixed up, although it is suggested that it was the use of salted herring barrels to fire a kiln. The effect is best on stoneware with high silica and iron. Salt glazes are achieved by adding common salt into the kiln at the maximum temperature. It splits into sodium and chlorine, the sodium reacts with the surface of the body to form sodium silicate glaze while the chlorine disappears up the chimney. It is rather more difficult to achieve a high quality glaze using salt as it tends to be pitted, resembling orange peel. The addition of red lead to the salt improved the finish. Adding pigmented slips to the stoneware body can colour the otherwise colourless salt glaze. In Germany in medieval times the potters initially achieved a yellow to rich chestnut finish, and later they used a cobalt wash before firing to achieve a blue colour. Salt glaze was probably used in Europe on stoneware as early as the 13th century AD.

Generally, while feldspathic glaze was used on stoneware in China, salt-glaze was used on stoneware in Europe starting in the Middle Ages.

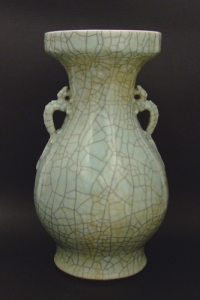

The colour of an initially transparent glaze once fired depends on the glaze type and condition of the clay at the surface of the pot with which it has reacted. If the pot is coated in an uncoloured lead glaze, then the resulting colour after an oxidizing firing will vary from pale yellow in the case of low iron clays to amber or brown with high iron clays. With a reduction firing, it will vary from pale yellowish-green on low iron clay to dark olive green on a high iron clay. The glaze almost always fuses to the body, so it is important to try to match the coefficients of expansion of the body and glaze as near as possible to reduce the likelihood of the glaze cracking and the surface of the pot becoming “crazed”. However, alkaline glazes are prone to craze because of their relatively high temperature coefficient of expansion.

The Chinese sometimes deliberately induced this crazing of the glaze as a decorative device.

Earthenware, being porous, absorbs water over time that expands the body also causing the glaze to craze.

The earliest earthenware was always unglazed, as the glazing technology did not exist. However since then some wares are deliberately left in the unglazed or biscuit state, to keep liquids cool, especially water, and for general cooking applications. Perhaps the most notable unglazed stonewares were the Chinese Ming Dynasty teapots from Yi-Hsing, early Meissen red stoneware and Wedgwood fine-grained Jasper ware.